20/08/2013 | Writer: Zeynep Talay

I don’t know how the mothers of Uludere gave birth, but they seem to be brave, as were their children. Braver than the men who killed them, and those who won’t punish them.

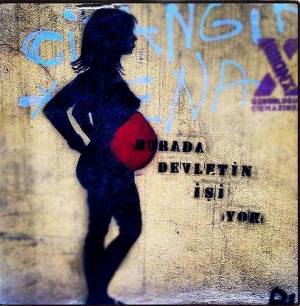

The birth of the new royal baby in the U.K. was covered in Turkey as much as anywhere else, and it would be easy to assume that that made it one of those media events that are truly global. But like most of them it was filtered through a local context. In our case it was quite a colourful one. Our prime minister, for instance, would approve of Kate, as he is a big fan of pregnancy, believing that all Turkish women should bear at least three children. On the other hand, recently a lawyer with religious commitments said on state television that heavily pregnant women should not be seen in public. Apparently it offends his aesthetic sensibilities.

Women in Turkey have had to listen to this sort of thing for some time now, and it is part of the reason why they have been so prominent in the recent protests. On the afternoon of June 1st I was in a crowd of tens of thousands struggling up the hill towards Taksim Square, where the police were firing tear gas in all directions. People were passing us in the opposite direction, teary, coughing and suffocating, and as we tried to help them our anger was growing. The chanting of the crowd grew louder, until someone shouted ‘Son of a bitch Erdoğan!’ A small group, including a good friend of mine, joined in. ‘Don’t say that’, I said to her. She replied: ‘I think he deserves it. What shall we do other than swear?’ ‘No’, I said, ‘swear at Erdoğan, but don’t use the word ‘bitch’’! My voice was then almost drowned out by those who agreed with me: ‘No swearing! More important, no sexist swearing!’

Once the police retreated from Taksim there were slogans everywhere. One said ‘We, the prostitutes, assure you that we did not give birth to Erdoğan.’ This was a reference to an incident that happened a few years ago. The mayor of Ankara, Melih Gökçek, was a guest on a live TV phone-in programme. As usual he was expressing himself in a crude way. At one point someone called in to say: ‘Gökçek, we came to a conclusion: Even if a group of us, forty prostitutes, joined forces, we could not possibly give birth to a man like you!’, and hung up. Gökçek had been talking about abortion, which he often does. In a more recent TV programme he refined his views. Asked what should happen to women who were pregnant as a result of being raped, he replied that the woman should kill herself before thinking about killing the baby.

Abortion is not on the agenda of the media and politicians in Turkey all the time, but somehow, every so often, a politician makes a ridiculous comment about it. One spectacularly absurd one came from the prime minister himself in May, 2012. He said, ‘Every abortion is an Uludere.’ What did he mean?

On December 29th, 2011, at 9.30 p.m. Turkish F-16s bombarded fifty Kurdish villagers in the village of Uludere (Kurdish: Roboskî) close to the Iraq border. They had mistaken them for terrorists. 35 people died, most of them children. In reality they were smuggling oil and cigarettes, as they have been doing for decades, as the local gendarmerie know very well. But that day the army made a ‘mistake’. When, instead of conducting a proper investigation, the government offered money to the relatives, the victims’ mothers protested: ‘We don’t want your money; we want you to find those responsible!’ They were ignored. On June 18th, 500days after it happened, when the mothers tried to go to the spot to remember their sons and nephews, they were kept out of the ‘incident area’ by the gendarmerie. The next day they received a letter informing them that they had been fined 3.000 TL each (approximately £1000) for trespassing. Even those relatives who didn’t go were fined.

So in May, 2012, Erdoğan is giving a speech to the AKP’s Central Women’s Committee. ‘We have written a legendary chapter in the history of women and politics’, he says. Somehow this brings him to the subject of abortion. He says he is against it, that abortion is murder and that it is planned by those who want to erase the Turkish nation from world history. Then he adds: ‘People keep talking about Uludere. Every abortion is an Uludere!’

So in May, 2012, Erdoğan is giving a speech to the AKP’s Central Women’s Committee. ‘We have written a legendary chapter in the history of women and politics’, he says. Somehow this brings him to the subject of abortion. He says he is against it, that abortion is murder and that it is planned by those who want to erase the Turkish nation from world history. Then he adds: ‘People keep talking about Uludere. Every abortion is an Uludere!’First of all, Uludere was not discussed in the media as much as it should have been. The people who did keep talking about it thought that the government should apologise and conduct a proper investigation instead of trying to silence people by giving them money. But Erdoğan thinks that everyone’s first and only criterion in this life is money, like his is. But I am still trying to understand how he connected Uludere with abortion. For a rational mind there is no such connection. On the other hand, if to show that abortion is murder he compares it with Uludere, then that is an admission that Uludere was murder too. An unsolved one.

When Erdoğan made this connection and made the discussion of abortion a matter for the media, it backfired and the AKP backed off from making abortion illegal per se. But they have already restricted the places at which it is legally possible (within ten weeks) and are making it easy for obstetricians to refuse a request for one. A more subtle measure was introduced in 2012 when the Ministry of Health sent letters to health centres saying that from now on, when a woman’s pregnancy test proved positive, the mobile numbers of the father and/or husband would be sent to the ministry. Their aim, they said, was to be able to track the health of the babies and their mothers. We found out about this practice when we read about an unmarried woman whose records had been mixed up with someone else. While she was visiting hospital for another health problem, the system generated an automatic ‘congratulatory’ call to her father informing him his daughter was pregnant. When she arrived home she was ostracized by her mother and beaten up by her father.

In 2004 Erdoğan himself wanted to criminalise Caesarian births. He had to drop it but his government continues to surprise us. On July 22nd the health minister Recep Akdağ said that he preferred natural births without painkillers to caesarians, on the grounds that ‘the more brave the mother is the more brave the child will be. We don’t want a generation of cowards.’ The association with the Roman emperor seems to have passed him by, but then the AKP aren’t very good at metaphors. I don’t know how the mothers of Uludere gave birth, but they seem to be brave, as were their children. Braver than the men who killed them, and those who won’t punish them.

Tags: women